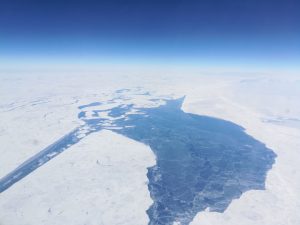

After a few days, I am getting used to life in McMurdo. It is a small village built on land but surrounded by sea ice and the ice shelf. There are quite a variety of buildings around the town, each with a specific purpose. There are field supply buildings, offices, cargo storage, carpentry buildings, gyms, a medical building, and fuel pump houses to name a few. So far, I have spent most of my time in the dormitories, galley, and in the Crary Science and Engineering Center where we have a work space. I have also been to several of the other buildings for training and to start to gather supplies for our work out at the airfield.

The dorm rooms here are comfortable. They have everything we need (bed, dressers, desk, and even a fridge). We share with one other person (happily, we sorted it out so it’s another member of our team).

And our team is all on the same floor, which makes it nice for gathering and communicating necessary information to each other. And, as far as dorms go, I probably have one of the most spectacular views possible out my dorm window, so I really can’t complain!

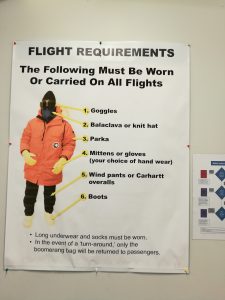

These first few days here have mainly been packed with training classes and getting to know our way around as we prepare to get to work. The environment here is very harsh AND we have to be very careful of our footprint here as we live and work in Antarctica. So, there is a lot to learn about! We have had briefings on fire safety, waste management, spill cleanup, outdoor recreation safety, IT setup, and the “Environmental Awareness, Field and Dry Valley Safety Briefing”. We have also had to take driver training classes so we can drive the big tire F350 trucks here on the ice, and snowmobile training – and then a safety training on driving both of those near the airfield. And, tomorrow, we have our last one: the “Antarctic Field Safety” class. All of these classes help us work and live safely around here and minimize our impact on the environment, in accordance with the Antarctic Treaty.

Other than that, I am just trying to get used to the cold (which isn’t too bad on a calm sunny day but can be wicked when it’s windy!!) and the constant daylight. We got here the day after the last sunset! The monitors where they list current weather conditions tell me that the next sunset is on Feb 20, 2018! Luckily our rooms have black-out shades, and I brought an eye mask, which helps a lot when trying to sleep. As for the cold, I always have my wool base layers on underneath my clothing and have been wearing my “Big Red” (the red parka they issue us) with hat, gloves, and neck warmer whenever I am outside.

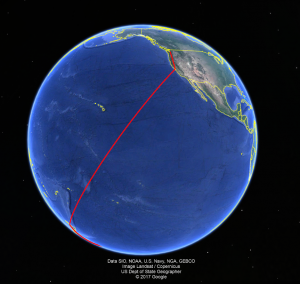

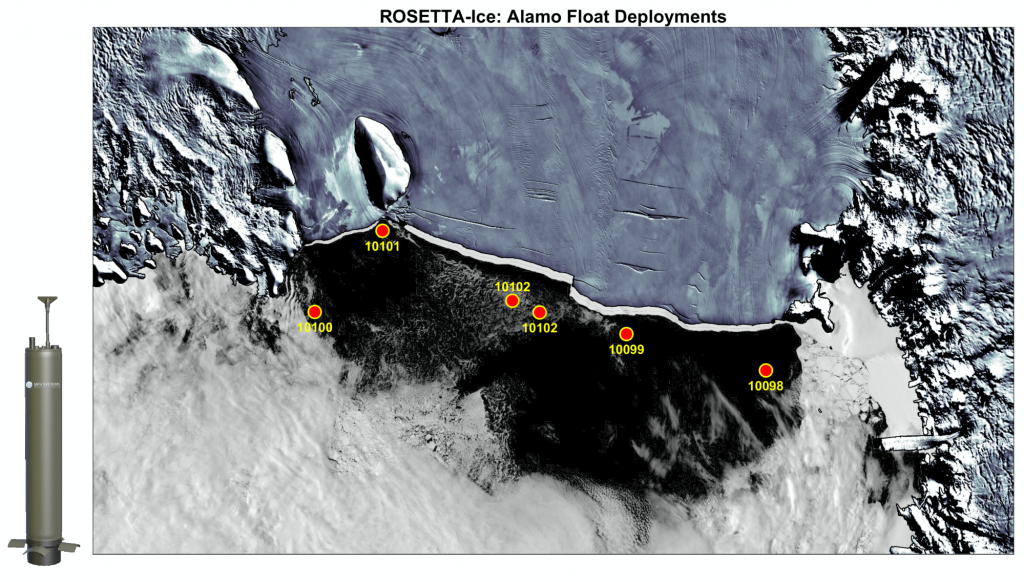

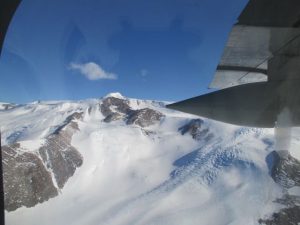

Our next big step is to get our work tent setup at Williams Airfield so we can start our flights out to map the Ross Ice shelf. Weather has been causing some delays, but they are predicting better weather tomorrow! So, with some luck, we will get our tent set up and fly our first check-flight on Monday.