Ross Ocean and ice Shelf Environment and Tectonic setting Through Aerogeophysical Surveys

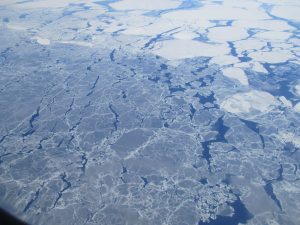

The IcePod focuses on properties of the ice shelf. We also measure tiny variations in the earth’s gravity and magnetism to learn about the surface of the earth that lies hidden beneath the ice shelf.

END OF POST

We finally get the word that we will get an airplane dedicated to flying the ROSETTA mission!

The LC 130 have a SABIR (Special Airborne Mission Installation and Response) arm, which allows attachment of specialized instrumentation packages like the IcePod.

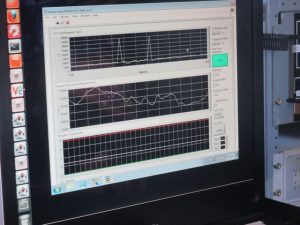

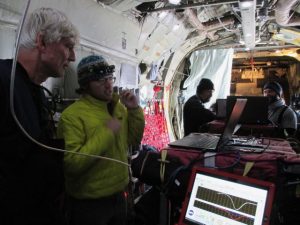

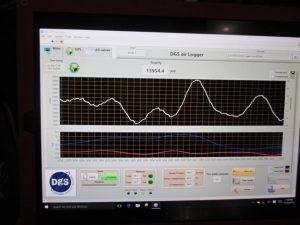

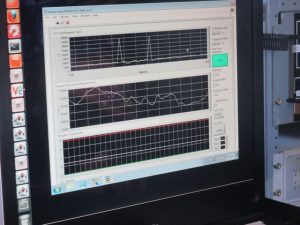

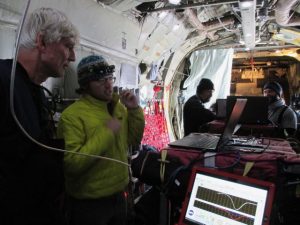

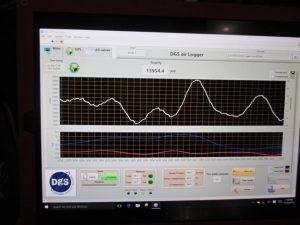

The IcePod is controlled by electronic equipment that is installed in a custom-build rack that fits perfectly against the curved inside wall of the airplane.

So what does the IcePod do? It provides a top-to-bottom view of the ice shelf. First, it has visible and infrared cameras that take images of the surface of the ice shelf. It has a scanning LIDAR, which shines a laser beam on the surface of the ice shelf and measures the time it takes for the laser light to reflect back, which allows us to measure the height of features on the surface of the shelf. It has a shallow ice radar, which emits a powerful radio signal that penetrates into the ice, and it listens for the reflections, which tell us about different layers of snow and ice in the upper part of the ice shelf. There is also a deep ice radar, which is at a different radio frequency, and penetrates to the bottom of the ice shelf, telling us where the bottom of the ice shelf is in contact with seawater. Finally, there is a navigation system to tell us very precisely where we are so that we can make accurate maps of the ice shelf.

The Observation Tube (usually called the Ob Tube) is a gateway to another world. It is a vertical metal pipe, or tunnel, through the sea ice leading to a small (one person at a time!) glass observation platform about 10-15 feet below sea level.

The Ob Tube is located just a couple hundred meters offshore of town, but, because it is on sea ice, safety procedures must be followed to visit it. The rules require that one travel with a buddy, perform a safety sign-out at the firehouse, and carry a VHF radio. After dinner one night a small group of us went to check it out.

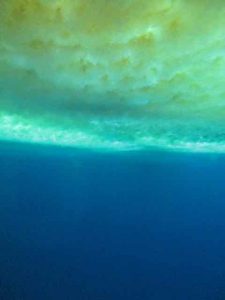

I went last. We had to tell each person when their 10 minutes was up. Everybody wanted to stay in the tube for longer, partly because it was much warmer underwater (just below freezing) than on the windswept surface of the ice. Mostly, though, they want to remain because it is really fascinating.

It was late evening, but the sunlight shone through the ice with a pretty greenish light.

Besides looking at the sea ice, I enjoyed looking at some large but delicate ice crystals that formed on the outside of the tube, and a large school of small fish that stayed just a little too far away to see very well. The most interesting thing, though, was hearing the pinging sound made by seals as they swam nearby. I did not see a seal underwater, but some people have.

Sea ice gets compressed against the shore near the southern tip of Pram Point sea ice is forced into the shoreline and crumples and breaks in features known as pressure ridges.

I took an interesting guided tour of this area. (Secretary of State John Kerry toured it a couple days after I did and pictures from his tour appeared in the New York Times and Washington Post.)

To a certain extent Ice can flow and bend but if it is stressed beyond a certain point it breaks.

The dramatic ice features are certainly very interesting, but there is more to the story. Weddell seals swim from the Ross Sea under the sea ice to find the gaps and holes around the pressure ridges. They haul themselves out on the ice, which provides them safe refuge from their predators (leopard seals and orcas) that swim in more open waters.

The relative safety of the sea ice makes this a good place to raise seal pups, and we came across several on our tour.

Weddell seals live further south than any other mammal (except for the few people who live at the South Pole) and Scott Base is the southernmost point in their range.

In some ways, I start my work day like a lot of people: I ride in a van pool about 9 miles to my office. But my public transportation is a snow-worthy 15 passenger van,

and my office is a tent on the McMurdo Ice Shelf.

The tent is heated, has electricity, and even has a (slow!) computer network connection. The front half of the tent is a rather typical office space; people working on computers.

The back half of the tent is for maintaining and storing our scientific instruments.

Our tent is at Williams Field (“Willie Field”), which is an airport with runways on packed and groomed snow. The planes that take off and land here have skis rather than wheels on their landing gear.

We work at Willie Field because our scientific study relies on the use of C130 transport planes, and we need to be near them to load and unload our gear and personnel for two flights per day.

When it is time for lunch, we walk about 5 minutes to “Willie Town”.

Willie Town is a small collection of portable buildings. Two important buildings are the galley (cafeteria) and the bathroom! The other buildings support airfield operations.

At the end of the workday a van picks us up and takes us back to McMurdo Station.

McMurdo Station is the largest settlement in Antarctica. It is like a tourist town in that its population swells in summer, but the summertime visitors are scientists, not tourists. As the research season gets into full swing the population can grow to over 1000, and right now it is 910. Some scientists are just passing through town on their way to Deep Field Camps. Some stay longer. Our group will be here about 5 weeks.

In some ways it resembles any small town — it has a fire station

, a medical clinic, a chapel,

two bars, a coffeehouse,

a fitness center, a library, a power plant, a sewage plant, and so on. There is even an ATM (cash machine), although there isn’t much to spend money on.

The architecture is strictly practical — most buildings have metal siding and shed roofs, although some are “quonset hut” style. The only building that is architecturally distinctive is the Crary Lab (mostly because it steps down a steep hill), and it’s not going to win any awards for exterior aesthetics. Most buildings are labelled with nothing but a number, which is pretty confusing at first, but it doesn’t take long to become familiar with every building you are likely to ever go into.

The busiest building in town is Building 155. Perhaps because of its importance, it is painted bright blue, which makes it stand out from the dull earth tones of all other buildings. Building 155 is the home of most administrative offices and the galley, where everyone eats all of their meals. The galley serves 4 meals per day — breakfast, lunch, dinner on a normal schedule, plus an additional meal called “midrats” (midnight rations) for people on the night shift. In fact, at 7 am most people are eating breakfast, but people on the nightshift are eating dinner. Similarly at dinnertime, the night shift people are eating breakfast. One is not supposed to eat the breakfast food at dinnertime unless one is on midrats.

By the way, the food is actually pretty decent — I especially like the fresh baked bread. There is a good variety at lunch and dinner and it is possible to assemble a reasonably healthy meal and, at least for now (while there are still frequent flights to and from New Zealand), fresh fruit and vegetables are available.

There is not a lot of snow in town as we head into summer. Ross Island is a collection of volcanoes, and the ground in town is red-brown volcanic rock. As long as it remains cold (say below 15 degrees F), the rock stays frozen in place. When we have warm weather (as we have had lately), the snow melts and the ground becomes a muddy mess. There is no asphalt or concrete pavement.

Upon arriving in McMurdo Station, we immediately attend our first orientation meeting. It is the first of many meetings to educate us on how to live in the potentially dangerous yet fragile environment of Antarctica.

We then pick up our baggage and find our rooms. Everybody shares a room, and two neighboring rooms share a bathroom. There is some shuffling of roommates and I end up rooming with one of my co-workers on the ROSETTA project.